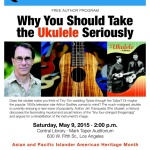

Why You Should Take the Ukulele Seriously

Jim Tranquada Interview: Why You Should Take the Ukulele Seriously

You may have seen our last blog post, about a talk ‘Why You Should Take the Ukulele Seriously’ in LA, that I wish I had been able to go to. As I live too far away, I wanted to get the nuts and bolts of that talk, and I thought others might also be interested to read it. So, thankfully, Jim Tranquada agreed to answer a few of my questions. I hope you enjoy reading the answers as much as I did:

1. Your Great-Grandfather was Augusto Dias. He is Ukulele Royalty. For those who don’t know about him, please tell us about him.

Augusto was born on the island of Madeira in 1842, the son of a barrelmaker. Nineteenth century Madeira was a troubled place, enduring the pressures of overpopulation, two infestations that devastated the vineyards, famine, and a major cholera epidemic. It’s not surprising that he, the woman who would eventually become his wife and their four children were among the first Portuguese recruited by the Hawaiian Bureau of Immigration as contract workers (that is, cheap labor) for the sugar plantations. The irony was that Augusto (a cabinetmaker by trade) and the vast majority of the other people aboard the Ravenscrag – the ship that took them to Hawai’i in 1879 — were from the city of Funchal, and had probably never set foot on a farm before. Like so many others, Augusto set up shop in Honolulu as soon as his contract was over. As a recent immigrant with limited resources, he set up a furniture and guitar shop in Chinatown, then considered Honolulu’s worst slum.

He and his friends Jose do Espirito Santo and Manuel Nunes were the craftsmen who first made and sold Madeiran machetes in Hawai’i – what quickly became known as ‘ukulele. Augusto was unlucky – he lost his shop and all of his inventory twice, in the Chinatown fires of 1886 and 1900, and his only son died an alcoholic in his early 20s. He also seems to have been a magnet for trouble. In 1892, a member of a gambling ring unsuccessfully tried to stash some evidence in his shop while being pursued by the police; seven years later, Augusto ended up in court testifying in the case of the man accused of trying to dynamite the Portuguese consul’s home. He was also a short man, only 5’5”, with a short man’s temper – he once shoved a guy through Santo’s shop window during an argument.

Augusto could not only make instruments, but he could play. According to family legend, he played for King Kalakaua in the royal bungalow on the grounds of Iolani Palace. That, the story goes, is how he got addicted to booze and the high life. His alcunha, or nickname – the Portuguese are big on nicknames — was O Santinho, the little saint, because he wasn’t. He was very strict with his six daughters, however, insisting on a strict chaperone system until they were safely married.

Dias ‘ukulele are the rarest of those made by the three original makers. I’m aware of 10 known examples, including the flamed koa instrument he made for his oldest grandson Charlie Gilliland in 1895 – the last one in the family – and two in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu.

2. You saw the completion of the book, Ukulele: A History. It’s credited to John King. Please, tell us about the writing of that book, and how it all came about/got finished.

Like many members of the modern ‘ukulele community, John and I met online. I had discovered his Nalu Music website and sent him an email in January 2002, which quickly turned into a regular correspondence when he realized I shared his obsession for ‘ukulele history. I had started working on an article for the Hawaiian Journal of History and suggested we join forces, which we did. After we submitted the article, we both had the same idea: maybe there’s a book in this. Naïve as we were – two independent scholars with no advanced degrees and a very thin record of scholarly publications – we put together a proposal and submitted to the publisher we thought the most likely, the University of Hawai’i Press. The proposal was accepted in the summer of 2003, and off we went.

Writing consisted of exchanging emails – ideas, outlines, draft chapters. (I live in Los Angeles; John lived in St. Petersburg, Florida. We didn’t meet face to face until 2004, when we both attended Uke Fest West in Santa Cruz.) It was a lengthy process, since John and I were researching and writing in our spare time, late at night, on weekends and vacations. We’d only completed two chapters when John suddenly, unexpectedly, tragically died in April 2009. I owed it to John and myself to finish the book, so I did. It’s really a tribute to his memory.

3. What were the top unreported facts you learned during the process?

What prompted us to write the book was the sense that there were very few facts associated with the history of the ‘ukulele. What passed for history was just a mix of misconception and myth that had been repeated for so long that everyone took it for the truth. Many people have commented on, and certainly wondered about, the number and extent of the footnotes in the book. John and I wanted to make sure that everything we wrote was fully documented, from original, contemporary sources whenever possible, so readers could have confidence in what we were saying and could go back and check the sources for themselves. (Footnotes are also the ideal location for bits and pieces that would otherwise clog up the narrative, but are just too good to discard.) In the largest sense, the top unreported fact about the ‘ukulele is that it has a real history.

4. How did you come to play the ukulele? What does it mean to you?

You could say it runs in the family. My father’s father, who could remember visting Augusto’s ‘ukulele shop on Union Street in Honolulu, played the ‘ukulele as part of a Hawaiian quartet to help pay for college, and my father on his first date with my mother actually took her out in a canoe and played the ‘ukulele and sang to her. (I’m glad to say she married him anyway.) I didn’t start until I started poking into the family history as an adult. The sad truth is I’m a lousy player, but when I pick up my uke – it’s a remarkable replica of one of Augusto’s early instruments, light as a feather and remarkably loud, made by Michael DaSilva – it’s not just a musical experience for me. It’s a picking up a tie to my family history. It’s kind of cool to be able to say that people in my family have been playing the ‘ukulele as long as there has been a ‘ukulele. Even if I am playing very badly.

5. Why should people take the ukulele seriously?

In the United States, Tiny Tim is the reason why most people in the United States don’t take ‘ukulele seriously. (The UK equivalent is George Formby.) Since Tiny Tim’s TV debut on Laugh-In in 1968, he has always provoked strong reactions.

Life magazine called his debut album “one of the most dazzling albums of programmed entertainment to come along since Sergeant Pepper,” while Time called him “the most bizarre entertainer this side of Barnum & Bailey’s sideshow.” He still provokes powerful reactions today within the ukulele community, with indignant partisans on both sides of the argument.

Regardless of the passionate feelings he inspires in the ukulele community, among the general public, most people regard him as a falsetto freak show. He is the first thing – sometimes the only thing — people think of when the ukulele is mentioned. He’s certainly the first thing newspaper reporters think of, almost 50 years after his brief career flowered and died. I once checked more than 40 stories on the ukulele that appeared or were aired in major print and radio outlets between 1998 and 2010, including The New York Times, USA Today, NPR, the L.A. Times, even the National Post up in Canada. All but three of them prominently mentioned Tiny Tim.

But what I think of is the Hawaiian National Band – Ka Bana Lahui – which was formed in 1893 by former members of the Royal Hawaiian Band after the overthrow of the monarchy.

The Provisional Government required all band members – who were government employees — to sign a loyalty oath to the new government, and most of them refused. They were instantly dismissed. Undaunted, they quickly acquired a new set of instruments, and began to perform on a regular basis throughout the Islands, becoming a rallying point for native Hawaiians, the vast majority of whom also supported the monarchy.

In 1895 they went on a tour of the mainland to try and rally support for the restoration of Queen Liliuokalani. As the band said in a statement while performing in Dallas at the Texas State Fair, its mission was,

“to let the people of this country judge whether the natives of the islands are a barbarous, ignorant, uncivilized tribe, with cannibalistic tendencies, or an enlightened and educated race of people who have been deprived of their property, their liberty, and their country by an intriguing lot of foreigners masquerading before the world in the virtuous garb of the missionaries.”

The 40-piece band was “double-handed” – that is, each member could play more than one instrument, a brass or reed as well as some kind of string instrument – including the ‘ukulele. By 1895, most ukuleles were made of koa. Koa is a tree indigenous to the Islands, originally used for canoes. In the 19th century, cabinetmakers discovered its beauty, and it quickly became closely associated with the Hawaiian royal family.

Hawaii’s first royal throne was made of koa; Hawaiian kings and queens slept in koa beds, sat in a koa pew in church and were buried in koa coffins. The impressive main staircase at Iolani Palace is made of koa. Koa became a symbol of aloha aina, or love of the land.

Playing on a koa ukulele was an act of Hawaiian patriotism, like displaying the national flag. That was particularly true when those songs featured protest lyrics – sometimes veiled, sometimes overt. The most famous of the period is “Kaulana na pua,” “Famous are the flowers,” a tribute to the band boys’ refusal to sign the loyalty oath that is still played today.

Here are the lyrics of the third verse. If you don’t speak Hawaiian, this would likely sound like any other song about flowers and mountain mists:

A’ole a’e kau i ka pulima

Ma luna o ka pepa o ka enemi

Ho’ohui aina ku’ai hewa

I ka pono sivila ao ke kanaka

But here’s the translation

Do not fix a signature

To the paper of the enemy

With its sin of annexation

And the sale of the civil rights of the people

Keep in mind that the band was playing this and other counterrevolutionary songs at a time when people were being thrown in jail for criticizing the provisional government, and government informers were filing regular reports to the Interior Ministry about the band’s potentially subversive activities.

This is all a far cry from “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” or “Leaning on a Lampost.”

I highly recommend you grab a copy of the book Ukulele: A History, you can do that here:

(I wasn’t paid or given any gifts to say that.)